In the most recent round of our essay competition for high school students, we received thousands of entries. We reached out to the authors of the highest-scoring essays to learn more about the stories behind their standout success.

On paper, the essays arrived quietly. Uploaded late at night or squeezed in between school and homework, they appeared first as documents with titles, footnotes and structured arguments. Behind them sat something more human: young people trying to work out where they stand in a world shaped by algorithms, institutions and inherited assumptions, and what it might mean to respond to it.

Ifrah Karim: Choosing the unfamiliar

Ifrah’s interest in psychology and human behaviour shaped her instinctive direction, but the question she chose deliberately pushed her beyond familiar territory. “The topic I chose – how rehabilitation programmes help prevent former prisoners from committing more crimes – was something I had never studied in depth before, which made it particularly intriguing.”

Her essay examines how rehabilitation programmes operate in practice, drawing on psychological theory to explore why certain approaches are more effective than punitive ones. This curiosity shows up clearly in the way she frames her argument, writing that rehabilitation works because it “targets the root causes of criminal behaviour and equip[s] people with the tools to build a different future,” rather than relying on punishment alone. Rather than asking whether people can change in the abstract, she focuses on how behaviour is shaped by environment, support structures and long-term intervention.

What drew her in was not a single class or conversation, but a pattern she began to notice. “Around the same time, I noticed several short videos and articles about rehabilitation and its impact on criminals, which further sparked my curiosity.” Writing allowed her to move beyond surface-level narratives and into the complexity beneath them.

“Writing this essay allowed me to explore how these programmes work, their role in transforming lives, and the challenges involved.” The process helped clarify her interest in applying psychology to real-world systems, particularly those connected to justice, policy and social change.

One of those systems will likely be technology. She already sees her long-term future in computer science, with a particular focus on software development and artificial intelligence, and is motivated by how these tools can be applied to real-world problems.

Read Ifrah’s essay here.

Vedika Arora: Finding the evidence behind your beliefs

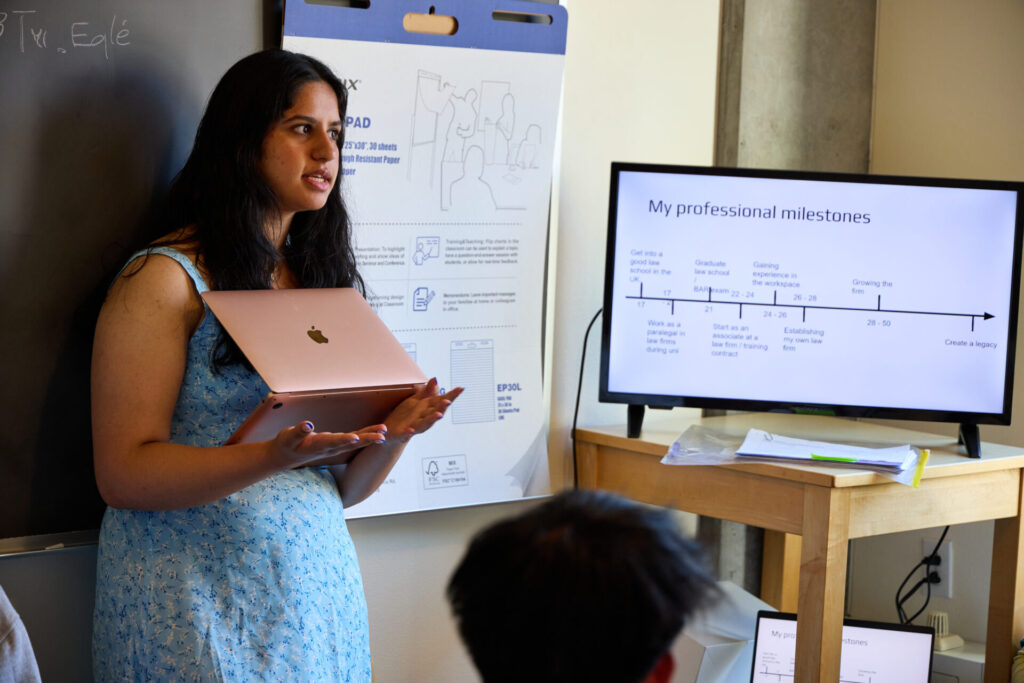

Vedika’s essay began with sustained exposure rather than a single moment of inspiration. After spending two years teaching legal literacy to more than 5,000 students across Delhi, she kept encountering the same frustration: constitutional guarantees that failed to translate into lived reality. When India passed the Women’s Reservation Act in September 2023 after a 27-year struggle, she saw an opportunity to test that frustration against evidence.

“I started with the hardest question: not whether women’s reservation (reserved seats for women in local government bodies) is morally right, but whether it would actually work institutionally.” Choosing the question meant resisting the pull of advocacy and starting instead from institutional performance.

Her essay examines whether constitutional intervention can dismantle structural barriers where voluntary measures have failed, drawing on empirical data from India’s panchayat reservation system. She focused on evidence precisely because she did not want the argument to rest on belief alone. “I wanted evidence along with arguments,” she explains, engaging closely with empirical studies to understand what actually changes when women hold political office.

The biggest challenge, she notes, was avoiding the temptation to argue for what she wanted to be true. “The hardest part was accepting that good policy requires acknowledging uncertainty, not performing certainty.” Writing the essay required cutting claims she could not substantiate and taking critics seriously rather than dismissing them.

Through that process, she realised that her interest lay less in moral positioning and more in institutional outcomes. “I learned I’m less interested in what should happen morally and more obsessed with what actually works institutionally.” The essay clarified her desire to work at the intersection of constitutional law, policy implementation and public communication.

Her choice of question also points directly towards her future plans, including building legal literacy infrastructure within India’s education system and entering government. Understanding how policy is communicated, scrutinised and debated through journalism is central to that goal. For Vedika, choosing the right question was not just an academic exercise, but a way of testing how ideas move from paper into practice.

Read Vedika’s essay here.

Maryam Arif: Questioning what gets lost in adaptation

Maryam’s essay emerged from a long-standing relationship with books, and a frustration she found herself returning to whenever a familiar story appeared on screen. “My essay focused on the question whether film adaptations truly resonate with the original novel.” As a cinema enthusiast as well as a reader, she was less interested in ranking books above films than in understanding why certain adaptations succeed in making a story feel newly alive. Looking at works such as Pride and Prejudice, Romeo and Juliet and Little Women, she became interested in how deliberate departures from the text are often made to speak to a contemporary audience, rather than to betray the original.

That instinct shapes the way her argument unfolds. Early in the essay, she writes that “adaptation is not photocopy; it is reading in light, sound and bodies,” framing film not as a lesser translation but as a different mode of interpretation altogether. Rather than asking whether adaptations are faithful, she examines what each medium makes possible, tracing how landscape, spectacle and authorship allow filmmakers to surface themes that are already present in the text but expressed differently on the page.

Choosing this question also forced her to confront her own resistance to academic constraint. She describes structure as the biggest challenge, particularly learning to balance personal insight with critical evidence. That process is visible in the essay’s close engagement with critics and theorists, from Linda Hutcheon to contemporary film reviewers, as she builds an argument that is analytical without losing its sense of curiosity. Writing became a way of slowing down her initial reactions to adaptations she loved or disliked, and examining what those responses revealed about authorship, interpretation and ownership.

Through the essay, she realised how much she enjoys working at the intersection of cinema and literature, and how much confidence she gains from sustained analytical writing. That confidence now feeds into a broader ambition to work in journalism, where careful reading, cultural criticism and clarity of voice matter. For Maryam, the essay was not just about adaptations, but about learning how to articulate why stories change, who controls them, and why those questions still matter.

Read Maryam’s essay here.

Join the Immerse Education 2025 Essay Competition

Follow the instructions to write and submit your best essay for a chance to be awarded a 100% scholarship.

Afsana Kabir: Taking inspiration

Afsana traces her essay back not to a personal experience she set out to document, but to something she read. “I was inspired by a previous essay winner who wrote about female leadership. Reading their essay motivated me to explore the topic in my own way and share my ideas.”

Rather than writing broadly about gender equality, she chose to focus on a specific policy and ask why it worked. Her essay examines Norway’s board quota system, using it as a case study to explore how binding legislation can succeed where voluntary measures fall short. “I wanted to show how policies, like Norway’s quota system, can create real opportunities for women to take leadership roles.” Choosing a concrete example allowed her to move beyond abstract commitments and look closely at outcomes.

The process of writing helped her clarify what kind of questions she wanted to pursue. “The essay allowed me to combine my interests in social issues, research, and writing while expressing my own perspective.” Rather than trying to cover every dimension of women’s leadership, she stayed with one policy and followed the evidence carefully, using data to test whether it delivered meaningful change.

One of the main challenges she faced was organising her research clearly. Planning and outlining helped her manage that complexity, but confidence came from something else. “Most importantly, I trusted my creativity, which helped me stay confident and express my thoughts clearly.”

Through the essay, Afsana realised that the most effective questions were the ones that allowed her to think rigorously while still speaking in her own voice. “I learned that I enjoy exploring social issues and expressing my ideas. I discovered I am more confident in my writing than I thought.” The essay strengthened her interest in leadership and equality, while also reinforcing the value of choosing a focused question that could support careful analysis.

Her future ambitions reflect that balance. While she plans to study computer science, she also wants to continue engaging with social issues and leadership, using research and critical thinking to create positive change. The essay marked an early moment of alignment between curiosity, confidence and direction, showing how starting from someone else’s idea can still lead to an original and meaningful question.

Read Afsana’s essay here.

Luong Manh Huy: Finding the history inside data

Luong Manh Huy’s essay began with a sense of unease about something often treated as settled. “The idea for my essay came from noticing how historical patterns of discrimination can quietly reappear in modern technologies.” As he learned more about machine learning, that unease sharpened into a question about where bias actually comes from and why it proves so persistent.

What pushed the topic from abstract to urgent were concrete examples. “Seeing real-world cases – such as unfair medical predictions or unequal risk assessments – made the issue feel urgent rather than theoretical.” These cases prompted him to look beyond surface-level claims about objectivity and ask how algorithms inherit bias from the data and assumptions that shape them.

Choosing the question meant narrowing his focus. Rather than trying to cover the ethics of artificial intelligence more broadly, he started with a clear research question. “I approached the essay by starting with a clear research question: how and why does bias emerge in machine learning systems?” That question gave the essay its structure, allowing him to move between technical explanation, ethical reflection and real-world evidence without losing coherence.

His essay draws on examples from healthcare, criminal justice and facial recognition to ground its argument, and examines different fairness metrics alongside their limitations. Writing it required careful judgement about depth and accessibility. “One challenge I faced was balancing the technical depth of the topic with the need to keep the essay accessible.” Deciding which details were essential became part of the analytical process itself.

He was also conscious of tone. “Another difficulty was ensuring the argument remained neutral and evidence-based, given how politically charged discussions about bias can be.” Revising repeatedly, seeking feedback and refining the structure helped him keep the focus on explanation rather than advocacy.

In the future, Luong hopes to pursue international education in fields that connect people across cultures, particularly global studies and future-focused innovation. For him, choosing this question was not just about artificial intelligence, but about understanding responsibility, inclusion and how systems built today shape opportunities tomorrow.

Read Luong’s essay here.

Majd Al Bitar: Leaning into instinct

Majd’s essay began with a pattern that unsettled him, one he kept encountering across different systems. “The idea grew out of noticing how biased algorithms quietly shape real decisions while remaining shielded by technical and legal opacity.” What concerned him was not just the presence of bias, but how easily it became invisible once encoded into automated processes.

A specific case sharpened that concern. “The wrongful arrest of Robert Williams revealed how feedback loops can transform human bias into automated authority.” That moment pushed him to look more closely at how machine-generated decisions come to be trusted, and why accountability often dissolves when responsibility is distributed across code, data and institutions.

Choosing the question meant reframing how he thought about machine decisions altogether. “Through my research on algorithmic bias and responsible technology, I began thinking about machine decisions as hypotheses rather than facts.” From that shift emerged the idea of ethical interruptions, a way of pausing systems at critical moments so their underlying logic can be examined before harm occurs.

He approached the essay deliberately. “I treated my essay like an investigation.” Starting from real cases of algorithmic harm, he traced the technical and ethical patterns behind them to understand how bias becomes embedded in feedback loops. Narrowing the scope was essential. “Another challenge was narrowing the scope, since algorithmic bias spans policing, healthcare, finance, and more.” Anchoring the argument in concrete examples helped keep the analysis focused and rigorous.

Through the process, Majd learned something fundamental about his own motivations. “The competition taught me that I’m most driven by problems that blend technical depth with social impact.” Exploring algorithmic bias confirmed that ethical questioning is not separate from engineering for him, but central to it.

While he intends to pursue computer engineering and nanotechnology, his focus lies at the intersection of hardware, artificial intelligence and ethical design. Choosing this question was an early way of testing that intersection, and of committing to building technologies that are not only powerful, but accountable.

Read Majd’s essay here.

Nellie Fouksman: Questioning why good intentions stall

Nellie’s essay began with a frustration she kept encountering in discussions about women’s leadership. “The idea for my essay came from noticing how often conversations about women in leadership focus on quotas or legislation, but rarely on the culture inside the institutions themselves.” What interested her was not whether change should happen, but how it actually takes hold once policies are in place.

She was drawn to the 30% Club precisely because it challenged her expectations. Rather than relying on mandates, it offered an example of change emerging from within institutions. “I was inspired by the 30% Club because it showed that real change can begin from within, through persuasion, accountability, and shared commitment rather than force.” Choosing this case allowed her to explore a different mechanism of reform, one grounded in mindset and culture rather than compliance alone.

Her essay examines how reframing leadership as both ethical and strategic can shift behaviour inside boardrooms, and why voluntary commitment, when paired with accountability, can sometimes move faster than legislation. The question she chose sits in the tension between tradition and transformation, looking at how the same institutions that once excluded women can also become sites of change.

She approached the writing process intuitively at first. “I started with the first thought that came to me… I just opened a blank page and word-dumped everything I remembered.” That initial lack of structure was deliberate. Only once the ideas were on the page did she begin shaping them into a coherent argument.

One of the main challenges was cohesion. “I had paragraphs that were strong on their own, but they didn’t connect smoothly.” Reading the essay out loud helped her identify what each section was doing and how it contributed to the whole. Rewriting with that awareness made the argument feel more intentional and cumulative.

Through the process, Nellie learned something about how she thinks. “The hardest part was cutting things out because of the word count, which showed me that I enjoy exploring topics in depth.” Writing confirmed that her curiosity runs wide, and that she values developing ideas fully rather than arriving quickly at conclusions.

The essay also clarified her longer-term direction. By focusing on the 30% Club, she became interested in how change can be driven from within institutions, not just imposed from the outside. That interest now extends to education systems and youth policy, where she wants to understand how culture, accountability and communication shape whether reform actually takes hold. Learning how to turn complex ideas into “clean, confident writing” felt essential to that goal.

Read Nellie’s essay here.

Aarini Gupta: When surveillance stops feeling optional

Aarini’s essay began with an interest that was already taking shape before she started writing. “My essay explores digital surveillance laws and their effectiveness.” What pushed that interest into a concrete question was noticing how deeply surveillance had become embedded in everyday digital life.

“The catalyst for my choosing this topic was an interest in how digital corporations have bred an ecosystem of constant surveillance,” she explains, describing both the social pressure to constantly share personal updates and the behind-the-scenes tracking that keeps users engaged and monetised. The issue stopped feeling abstract when she recognised how closely surveillance was tied to attention, behaviour and profit.

Two sources sharpened that focus. “The initial spark was ignited when I watched the documentary ‘The Social Dilemma’ on Netflix and then went on to read excerpts from ‘The Age of Surveillance Capitalism’ by Shoshana Zuboff.” Rather than treating these as conclusions in themselves, she used them as entry points into legal analysis.

Her essay examines the balance between security and privacy in digital surveillance legislation, analysing how laws attempt to legitimise monitoring while guarding against overreach. Choosing this question meant narrowing in on consent and effectiveness, rather than attempting to cover every dimension of digital ethics.

Writing the essay required discipline as well as curiosity. “Try not to get overwhelmed by the magnanimity of resources you have to scour through – it’s easy to feel discouraged by that.” She limited herself to a small number of credible sources, revisiting them in depth before expanding further. Multiple drafts allowed her to refine both structure and voice.

Through the process, her interests began to crystallise. Her future plans follow directly from that focus. She hopes to pursue a career in the legal profession, with particular attention to digital ethics, privacy and the regulation of big technology companies. Choosing this question was an early way of testing that direction, and of learning how legal reasoning can be used to interrogate systems that are often treated as inevitable.

Read Aarini’s essay here.

Final thoughts

Across all of these essays, a pattern emerges. None of the writers claim certainty. Instead, they describe a process of testing ideas, of discovering the limits of their own knowledge and learning to sit with complexity rather than resolve it prematurely. Several mention moments of self-doubt: worrying their arguments were too narrow, too ambitious, too critical. Overcoming those doubts often meant returning to the question that first sparked the essay and trusting that it mattered.

There is also a shared sense that writing itself was a form of discovery. For some, it revealed interests they had not fully articulated before. For others, it clarified ambitions that had felt vague or inherited. The act of putting an argument on the page, knowing it would be read by someone else, forced a level of accountability that casual reflection does not require.

In a moment where speed is rewarded and opinions are often delivered fully formed, these essays read as something else entirely: records of thinking in progress. They show young writers pausing to ask how systems shape behaviour, whose voices are amplified or erased, and what responsibility comes with analysis. Long before any classroom discussion begins, the work has already started, quietly, in the act of writing itself.