What is the history of the NHS? And, why does it matter?

So, we have some rights. Inalienable, immovable human rights that all UN members have agreed on. Among several others are the rights to life, dignity, and medical care as needed.

Now, this may be controversial, but I’m not sure how paying for your healthcare is compatible with those entitlements. After all, in order to pay, one needs money.

In all countries without centrally controlled economies, there are significant inequalities in household incomes. Some people are rich; some are poor. While, in theory, all have the ‘right’ to healthcare, those in poverty have more hurdles. Trapped in a cycle of inadequate education, diminished career prospects, and a series of low-paying, low-skilled jobs with little hope of progression. With chronically lower incomes, a choice may arise between food on the table, and a visit to the doctor.

Related Read: Why You Should Be A Doctor?

What good is a right to healthcare if you can only get it by making impossible sacrifices? Where’s the dignity in having to go without electricity to pay for treatment, simply because you want to not die?

“None,” chorused the tea-swilling, monocled, moustachioed Brits of 1948.

Early State-Funded Care

The poor and infirm of England have long been cared for by the state, in some form or other. These arms of care began with monasteries, the main places of learning and healing in Christendom. Monks would found hospitals to care for the ill, both acutely and chronically. Until Henry VIII dissolved them.

During the reign of Elizabeth I, the 1601 Poor Law brought almshouses to the paupers, where they could again receive state-provided care. Until 19th-century Britain decided they were being too soft on them.

With the Poor Law Reform Act of 1834, the poor and able-bodied were sent to workhouses. Think of them as pauper concentration camps in Victorian England. The idea was to save the Treasury some money by scaring people into being less poor, and wringing some labour out of the destitute asking for state help.

Related Read: The Man Who Made Surgery Painless – Nikolai Pirogov

Later, the poor and sick were admitted to receive care, but the conditions were… Well, they weren’t nice. not ideal with poor hygiene and little training for staff.

The Voluntary & Private Sectors

By contrast, the rich had the luxury of being ill in their own homes. Since they could afford private physicians to tend to their needs, they feared not the hell of workhouse infirmaries. Instead, they had access to the best care in sublime comfort, an example of early inequalities in the system.

The workhouses provided one of two healthcare options for the sick and poor. The other option, rising in parallel with the workhouses, was the voluntary hospital.

Some began their lives as monastic hospitals and were re-founded after Henry VIII’s dissolution; others were founded by philanthropic men who hoped to help the poor with their care – including Addenbrooke’s in Cambridge, one of England’s earliest voluntary hospitals still running today.

Now, because these two arms of care were funded differently, they admitted different patients. The voluntary hospitals, despite large donations and endowments of land from the Crown, could not afford to treat the chronically ill or dying.

Therefore, the acutely sick went to the voluntary hospitals, leaving the chronically ill, disabled, or elderly to seek the more stably funded workhouses for their care.

Finally, in 1911, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, put in place a system of National Health Insurance. Working males of a certain age would pay into this pot of money, and this would entitle them to free care from any doctor listed on a local panel. But their families weren’t covered, just the employee.

As I hope you’ll see, this was a very confusing system of healthcare with several streams operating in parallel, and not everyone could access all of the services!

The Rise of the NHS

Due to the threat of high casualties from Luftwaffe bombings in the Second World War, the hospitals and voluntary ambulance service in London was reorganised into the Emergency Medical Service in 1938. The workhouses and voluntary hospitals were all commandeered for the service, with staff moving freely between the two breeds.

This, coupled with government-funded upgrades, made the prospect of practicing medicine within the formerly grim and grimy workhouses, far more palatable to the staff of the later NHS.

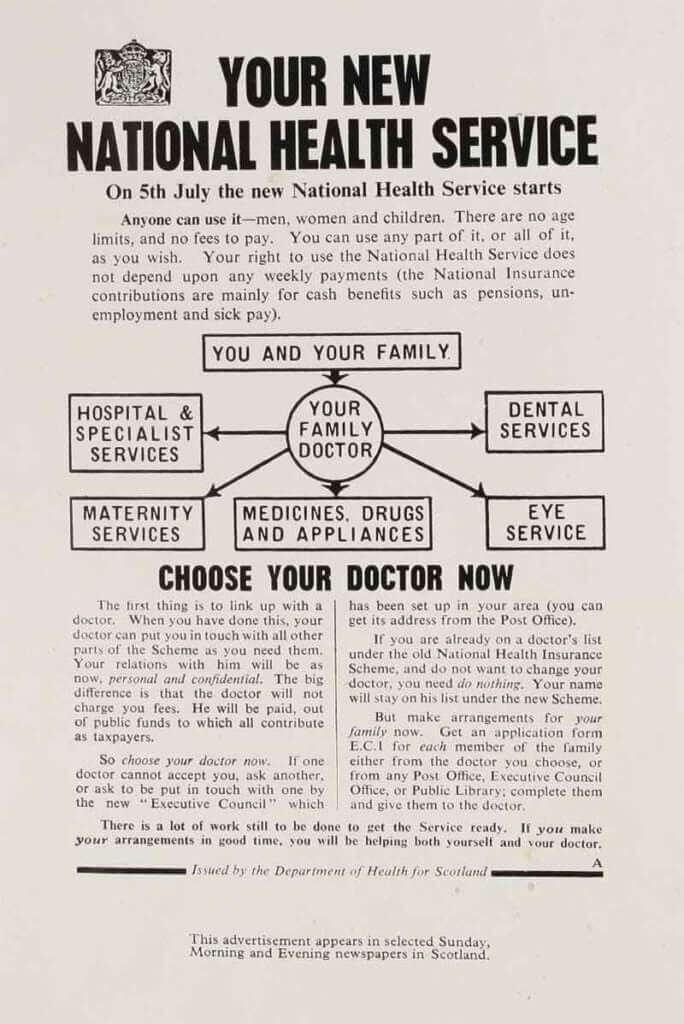

After the war ended, the Labour government established the National Health Service on 5th July 1948. Central funding was provided to the majority of the hospitals in the land, the system of National Health Insurance was transferred over to the new service, and suddenly everyone could see a physician, access forms of social care, or enter hospital for free.

Suddenly, the chaotic and disparate streams of healthcare were brought together and paid for, so that the British people would have no need to fear debts that once accompanied illness.

Join the Immerse Education 2025 Essay Competition

Follow the instructions to write and submit your best essay for a chance to be awarded a 100% scholarship.

Importance to Medicine

Yes, much research is conducted in NHS hospitals. Yes, the NHS pays for the education of new doctors and nurses. And it even set an example for other state-run models across the world. But it represents far more than that.

The NHS promotes an ideal, rather than an academic concept. It paints a picture of a world where healthcare is provided to all who need it, regardless of wealth. It speaks to the meaning of the field, rather than the growth of its powers.

You May Like: What Is It Like To Be Studying Medicine At University?

In a world dominated by Brexit, economic uncertainty and short-term, headline-grabbing political games, we would probably do well to remember the long story of the NHS. In many ways, it’s a story of Britain and a story of medicine itself. It was born, not from violence and division, but in spite of it. In opposition to it.

The NHS is humanity making itself heard among the echoes of marching boots and silver coins. It’s an aid for the sake of aid. It’s toiling without hope of riches and glory. It’s a Britain that cares about its citizens’ rights to life, dignity and medical help. It reminds us what medicine is meant to do for everyone, be they rich or poor.

Interested in Learning Medicine or Biology?

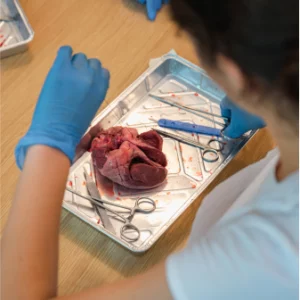

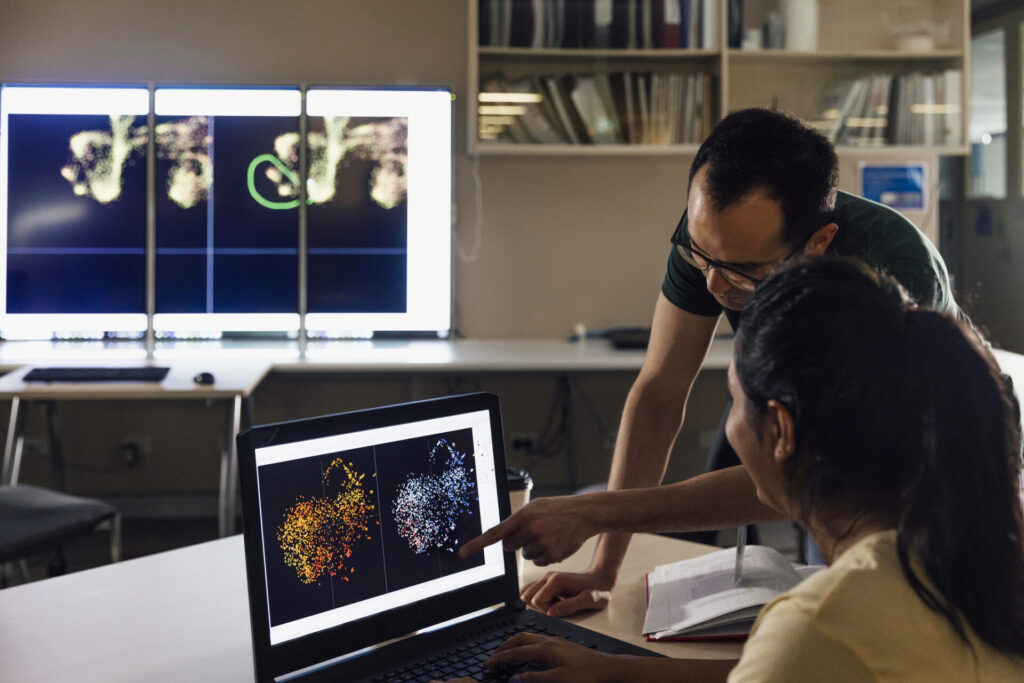

Are you intrigued by the history of the NHS? Does the field of Medicine or the science behind living organisms attract your interest? Why not sign up for our Medicine Summer School? There you’ll explore in-depth topics in medical technology.

Sources

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08d91e5274a31e000192c/The-history-and-development-of-the-UK-NHS.pdf

https://historicengland.org.uk/research/inclusive-heritage/disability-history/1832-1914/the-changing-face-of-the-workhouse/

https://www.londonlives.org/static/Hospitals.jsp

http://www.nhshistory.net/poor_law_infirmaries.htm

https://www.historyextra.com/period/modern/the-nhs-what-can-we-learn-from-history/

http://www.nhshistory.net/ems_1939-1945.htm

https://navigator.health.org.uk/content/1601-1911-poor-law-rise-voluntary-hospitals

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/jan/18/nye-bevan-history-of-nhs-national-health-service